Peering Into The Vault

Peering Into The Vault

We have recently been welcoming guest bloggers to our site (because of this).

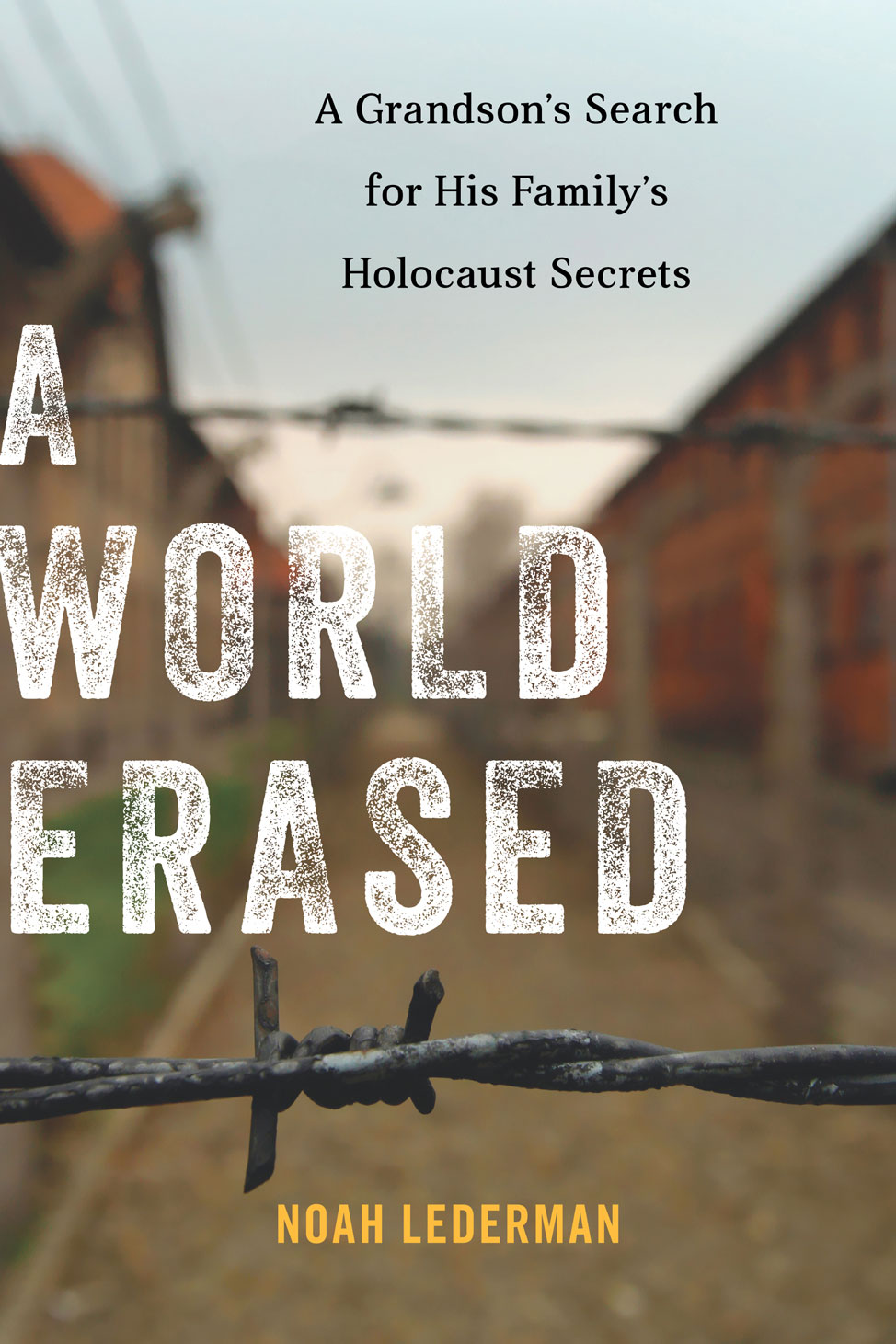

Noah Lederman, the grandson of Holocaust survivors, had always wanted to hear his grandparents’ stories of survival. But they refused to share their traumatic memories with him. As a youth, Noah couldn’t find a way to access that past. But after college, Noah traveled back to his grandparents’ hometown of Otwock and to many of the sites where his grandparents had been persecuted, including concentration camps like Auschwitz and the Warsaw ghetto. Through travel, Noah was able to glimpse the past and convince his grandmother to share her stories before it was too late.

This is an excerpt from A World Erased: A Grandson’s Search for His Family’s Holocaust Secrets, published February 7, 2017 by Rowman & Littlefield. This extract takes place in 2004 on the streets of the former Warsaw ghetto. The Philadelphia Inquirer selected A World Erased as one of the best books of the year, and Booklist called it “a vital contribution to Holocaust collections.”

“Mom,” my father begged, “Daddy doesn’t want to see you go to the bathroom.”

“Sha! Quiet. He does what I want,” she hollered.

“At least now it’s without objection,” Dad told the rest of us.

After that Seder, Grandma stopped cooking completely.

“Who should I cook for? Poppy’s dead.”

We grandchildren were all slightly offended.

That was four years earlier, when the depression occupied her heart like an open wound. While it had been evident that each of us thought we were Poppy’s favorite grandchild, most would happily concede that I was Grandma’s. The other grandchildren got annoyed with her noodging; I never tired of it and instead found that the kvetching was a source of both humor and love. When Grandma had cooked, I was also the last to say that I was full. That earned me points as well. Certainly, I thought, my return after fifteen months overseas would have some positive effect on Grandma’s mood.

I buzzed 15K and rode the elevator to her floor. Grandma met me at the door. She poked her head out into the hallway, opening the door just enough to hug me and kiss me and allow me to enter. It was as if she were trying to contain Poppy’s spirit.

“Oy Noiach, I missed you. You had time to visit Poppy.” Saying “Poppy” had brought tears to her eyes and cracked her voice with conspicuous sadness. She collapsed into the melancholy that I had left behind more than a year before. Nothing had changed.

Grandma looped her arm through mine, and I led her back to the kitchen table, where Poppy stood in his frame. He also still dangled in the gold around her neck. His blue eyes and lion’s smirk shone.

“Where’s your father?” Grandma asked.

“He’s parking the car,” I said.

She shrugged as if she knew his plan: delaying arrival by parking far and taking the long route down the boardwalk.

“Grandma has no food for you,” she reminded me. The faithful pot of chicken soup simmering on the stove and the purple jar of horseradish that stood guard beside the pool of gefilte fish had long vanished from her apartment.

“Don’t worry, Grandma. I just wanted to see you. I missed you.”

“You still should eat.”

My father arrived. Within ten minutes, he had opened all the mail and written the two checks for both bills, guiding Grandma’s hand so that the pen rattled along the signature line.

“Look how I shake, Noiach. Ever since Poppy…” The name Poppy caused her to blare. It cut short the rest of her sentence.

“Your hands always shook, Mom.” Dad began pacing the apartment, already preparing to leave.

“Look,” she said, holding up her trembling hands like evidence at a trial.

“They shook when dad was alive, too.”

“Oyyyyyyyy. Now the shaking is worse. Noiach, I swear.”

“I believe you,” I told her.

My father looked at his wristwatch. “I can’t do this for an hour.” He walked out onto the terrace.

While Grandma regained her composure, I went into her bedroom and revisited the familiar faces of my murdered family above the light switch. I could not imagine living Grandma’s life. Death after death after death after death… a spell of happiness… and familiar death once more. And then she herself, the woman who willed her own demise, could not die.

“Can I tell you about my trip?” I asked Grandma when I returned to the table.

“Forty-nine minutes,” my dad shouted from the terrace, counting down that which remained of our visit.

“Were you safe?” she asked.

“I was safe.”

“Did you eat well?”

“Not as well as I eat here.” I poked her in the arm a few times and gave her my favorite-grandchild smile.

“Grandma don’t cook anymore. You Poppy’s dead,” she reminded me.

“I know, Grandma. Not as good as I once ate here.”

“Do you remember Poppy?”

“Of course I remember Poppy.”

“He’s dead.” She let out another whimper.

My father came back inside and flipped through the bills just in case he had missed anything. He could think of nothing worse than returning outside of a scheduled visit because of an overlooked bill. But after Grandma let out a fifth “Oy,” Dad slapped his side and banished himself to the terrace for the remainder of our stay. Grandma looked up at me like a helpless animal dying in a trap, shrugged, and then pointed at the picture frame.

There was no more finding humor in her neuroses. This was pure misery. Even I couldn’t listen to her grieve for an hour. Not four and a half years after Poppy’s death.

I pulled my notebook from my pocket, one that I had filled with questions after visiting the camps and ghettos. The questions, I assumed, would go unanswered. But I wrote them down while in Europe because it was better than allowing them to swim around my mind. I tapped the book’s cover.

Would reminding her of a pain so distant be fair, especially now when her entire life was filled with hurt? But then again, how much worse could a life be than the one Grandma was forced to maintain?

“Grandma, did I tell you that I visited Poland? I went to Otwock, Warsaw, and Auschwitz.”

Her face stiffened up.

“You went to Otwock?” It was the first time during the whole visit that I had heard her speak without self-pity. She said the name of her former town using that Latin pronunciation with postcard-like flair: Oat Vox, where the air is pure and serves as a lovely destination for those who need to inhale the freshness of the Swider River. “Did you see the Umschlagplatz?” Her eyes lit up like a child’s who had just inquired about the details of a trip to Disneyland.

“I… I saw the Umschlagplatz. You mean the one in Warsaw, right?”

“Of course the one in Warsaw. The Umschlagplatz.”

Of all the things she could have wondered about, I had no idea why she chose that site in the Warsaw ghetto, where the Jews had been rounded up for transports and sent to the concentration camps. I had no idea why this place of death had brought a sparkle to her eye.

Grandma smiled. “I can’t believe you saw the Umschlagplatz. You know, tatehla, this is where I was.” She had made this antechamber to the camps seem like the happiest place on earth. And the Umschlagplatz, which gave her pause from mourning Poppy, did, for one brief moment, feel like the grounds of jubilation.

“What do you remember about the Umschlagplatz?” My arms tensed, my fingers gripped the pen. I was ready to write every word.

Her smile faded immediately and she settled her grave eyes upon me. “Many things, Noiach, many things.”

I had almost skipped over visiting the site of the Umschlagplatz. It hadn’t been on my Warsaw map and on first pass, from across the street, I figured that the white and gray walls of the memorial set like a roofless cattle car was some sort of incomplete strangely designed store. On my second pass, since the sites in the city dedicated to the Jews were few and I was slightly curious about the structure, I crossed the busy road and inspected what turned out to be the memorial.

“Grandma, do you mind if I ask you a few questions?”

“What’s to ask?” she said, as if she had grown up during the twentieth century’s most uneventful decades.

The Umschlagplatz of Warsaw appeared as if it would serve as our depot into the Holocaust.

***

After our day in Otwock, Gabriela and I woke the next morning in Warsaw. Gabriela was sick and spent the day in bed. I searched the city for any traces of its annihilated Judaism. But as I had expected, most of Warsaw’s Jewish past had been ripped up like uninvited weeds. The ghetto wall, the

one that had kept the Jewish population imprisoned in a dismal wasteland, had been dismantled except for one section that stood in the courtyard of an apartment complex like an eroded handball court. More attention, however, was paid to the drying of laundry on the terraces above.

Farther along, I found the large Jewish cemetery. But it was locked. After another twenty minutes of walking, I came across Mila 18, the famous bunker where fighters like Mordechai Anielewicz and some of my grandparents’ friends had planned their uprising. All that remained to mark that place of Jewish resistance was a mound of dirt, as if the bodies of those Jewish rebels had not stopped swelling in the ground. To me it was a miniature Polish Masada.

Despite this proud lump in the earth, I couldn’t believe what had been erased. Present-day Warsaw felt similar to what would happen if a church congregation took over a building that once housed a temple. The congregation would whitewash the walls of Semitic symbolism and change out the stained glass for scenes with Christ. Maybe they would overlook a doorframe, unintentionally leaving behind the grimy outline of where a mezuzah once hung. The section of ghetto wall and mound of dirt were

those oversights.

There were, however, a few intentionally constructed memorials. Down the block, a cenotaph of Warsaw ghetto fighters stood in a park, where one Pole walked his dog. He stopped beside me as I stared up at the sculpture of men prepared to die. One fighter clutched a homemade bomb; others displayed the countenances of those offering a silent battle cry.

“Where you from?” the Polish man asked me as his dog sniffed the steps that led up toward the sculpture.

I told him.

“America, heh? You must pay a visit the Stare Miasto tonight. It is the sixtieth anniversary of the Warsaw Uprising. Very proud moment in Warsaw. Very proud.”

“Did you say the anniversary of the uprising in Warsaw?” I was stunned.

“Yes, tonight. Very big event in our city.” He pulled the beagle’s leash, but the dog pulled back. He waited so that the animal could urinate on the monument’s steps.

But I pardoned this man’s affront to the dead Jews. His tone and the news of the celebration were more important than addressing the disregard he and his dog had for the frozen uprisers.

“They celebrate the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising,” I said aloud, shocked that the Jews were not completely forgotten.

Polish couples pushed strollers through the park. I was thrilled that these babies would grow up in a Poland that honored the Jews of the Warsaw ghetto. In the communist gray of the city, I saw sunshine. I felt the fool for having doubted the Poles to such extremes.

By evening, I arrived at the crowded Stare Miasto. Gabriela stayed back; her cold had worsened.

I stood stunned by the celebration held for the Jews. These people didn’t hate the Jews, I realized. Look how they celebrated and remembered what the Warsaw ghetto Jews had tried to accomplish. I swallowed an amalgam of relief, pride, and chagrin.

Families shuttled their children around the statue-filled promenade, explaining the stories connected to the bronze people. Kids in scout uniforms marched with pride. If I had owned a Jewish Star necklace, I would have worn it on the outside of my shirt instead of trying to conceal my

identity in Poland.

A mother pointed her little girl’s hand toward a statue of a boy wearing a bronze helmet too big for his head. He held a machine gun in his little hands.

“Who is this boy?” I asked the woman, already proud of the story that I had planned to exchange with the child and her mother about the uprisers whom I knew.

“Tell him, sweetie,” the Polish mother said to her daughter, having prepared her daughter to pay homage to the Jews.

“That’s a boy who was killed for singing songs,” the little girl said shyly and then pulled herself into her mother.

I thought up all the songs I had learned in Hebrew school. Had he been singing “Dreidel, Dreidel, Dreidel”? Or maybe a few choruses of “Dayenu”?

“He was killed singing patriotic songs while fighting for Poland in 1944,” the girl’s mother amended.

1944? I thought. I traveled back along the Holocaust timeline that I had committed to memory. Jews had been removed from Warsaw by April of 1943. By the following year, they were nearly an extinct people in this city, especially by August 1, the date of this Warsawian celebration.

“What exactly are you celebrating today?” I asked.

“Today is the anniversary of when the Poles fought back against the Nazis and pushed them out of the city for good.”

All of this—the streamers, the noise, the pride—had nothing to do with the Jews. It was a celebration of a people who had, prior to 1944 and forever after, been indifferent to the fate of the Jews. My heart dropped. That mixture of pride and chagrin and relief had lost its potency and spoiled into a fuel of confusion and hurt and anger.

The mother ushered her little girl on to the next statue.

I never realized that the Poles, who had waited for the Jews to vacate their homes, to leave behind their heirlooms, to bleed out in the ghetto, had finally fought back.

How foolish of me; I had nearly exonerated them in an afternoon. I wanted to go back in time and curse the man for allowing his dog to piss on the statue dedicated to the Jews.

The scouts paraded down the avenue. Candles, flowers, ribbons adorned buildings and fortresses. I exited the Stare Miasto and stopped when I had reached a gate. A garden of red candles had their flames lean with the wind.

A man in his early fifties bent down to light another wick. Grandma had always lit a white yahrzeit candle on Yom Kippur for her mother, who had been murdered only miles from this celebration.

“Who did you light the candle for?” I asked as though I were giving one more chance for someone to refute my anger.

“My mother.” The man spoke with an American accent. “I come back every year to celebrate this Independence Day. The Nazis imprisoned my mother because she fought for Poland. And you? Any connection to all this?”

I noted my exits and the direction in which the youthful Polish storm troopers marched. The roar of the festivities traveled away from the candles.

“My grandparents fought in the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising.”

He cleared his throat. “My mother was very fond of Jews. She never saw them as an alien nation. To her they were Polish.”

It seemed like the modern thing to say.

How could it have been that every Pole, from Teddy’s grandmother to this man’s mother, loved the Jews, yet my people were shipped so easily to the gas chambers? Why was it that each time Poppy snuck out of the ghetto and scurried around the streets of Warsaw in search of extra rations, some Pole shouted, “Jew”? How was it that the Polish revolution, honored by the flames we stood before, was delayed until the human smoke of my people became ubiquitous? I didn’t repay his words with the same kindness. I couldn’t.

Grandma once told me, “A good person is a good person… but there is no such thing as a good Polack.”

To call Grandma a Pole would have been more degrading than calling her a yid or a kike.

Poppy had always wondered how his own countrymen—even if they had cast the first and second and third stone, even if they had called him “dirty fucking Jew,” even if they had despised his people—could help send his four sisters, his father, his mother, his entire extended family, into the fires of Treblinka. His neighbors had ratted them all out to the Germans in exchange for a sack of potatoes and a few sips of schnapps. That had fueled the pilot light of Poppy’s hatred.

The gentleman who honored his mother stood beside me as we watched the flames leap into the sky of Warsaw.

***

“You Poppy was at the Umschlagplatz, too,” Grandma remembered as I read through my questions.

If the utterance of “Umschlagplatz” had pried open the Holocaust vault, the mention of Poppy threatened to slam it shut. I chose a question at random to change the subject.

“Grandma, did you ever spend any time in the Pawiak Prison?”

“I was never there.”

I had figured this much as the prison was mainly for non-Jews. But it moved us away from the P-word.

“When I was in the Warsaw ghetto I walked through this park—”

“There were no parks in the ghetto,” Grandma said, irritated. What do you think the Holocaust was? Parks? The Holocaust wasn’t a game of running bases.

“I know there were no parks . . . I mean, now there is a park.”

Grandma shook her head as if the rubble of the Warsaw ghetto still smoldered and the disease that had festered in that place decades ago forever made the Jewish quarter an untouchable Chernobyl.

“In this park there was this monument that had been dedicated to the Jews who fought in the uprising. It was this enormous bronze relief.”

“Relief. Oy. This was no relief.”

“Grandma. No. You’re…” I thought of the fallen fighters and the man who clutched a homemade grenade and the others who stood frozen in the Monument to the Ghetto Heroes. I would never tell Grandma about the metal panel on the reverse side of the black marble memorial, where a solemn procession marched from the ghetto into the gas chambers. “At this monument, I ran into a group of Israeli soldiers.”

Her weak facial muscles tightened slightly into a smile. The name of the Jewish homeland always produced at least a split-second respite from her misery. But Grandma, the living epitome of irony—a warrior in a housedress, a woman who found comfort in sadness, a survivor begging to die—smiled at the incongruity.

“Israelis? In Poland? Noiach, what should they want with Poland?”

“One of the soldiers told me that they were there to remember. First

I met them at Mila 18.”

“I have friends who fought with Anielewicz. You know Mordechai

Anielewicz?”

I nodded. “Grandma . . . What did you do during the uprising?”

“Oy.” She waved off the question with a force that I hadn’t seen in years, since lifting her hand to such heights off the table had become a painful chore. “Noiach, what you say to these Israeli soldiers?”

“I told them that I was there remembering my people, too.”

“That’s nice,” Grandma said. “What else these Israelis do?”

“After I saw them at Mila 18, they gathered beneath the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising monument, and a female soldier sang the Hatikvah.”

“This is the Israeli national anthem,” Grandma said, humming a few bars of the song. “I want to go to Israel after the war. But Poppy did not want to go. He say we go to America. We come by boat. There was such garbage on the shores. Filthy. Maybe if we go to Israel, there be less garbage and maybe Poppy be alive today.”

My father had entered the room in time to hear Grandma’s last five words, missing all the progress we had made. “He would not be alive today. He had a bad heart. He smoked and he was stressed. Come on, Noah, we need to go.”

“He’d be alive today if we go to Israel,” Grandma insisted.

“He would have died a young man if he went to Israel,” my father replied. “He just survived one war. Do you think he wanted to go and die in another one? You want to go to Israel, Mom, I’ll send you to Israel.”

“I want to go to Israel with Poppy.”

“I don’t think they’ll let him fly, Mom.”

Grandma stroked her shaking fingers across Poppy’s face in the frame, as if to shield him from the insult.

“They tried to draft Poppy into the Korean War,” Dad said. “You know what he did to avoid that? He convinced the army he was insane. He was not going to fight for Israel. The Holocaust should have been an automatic pass for survivors to avoid the army. They should have been guaranteed a lifetime of peace and happiness.”

“No more Poppy,” Grandma moaned. “Maybe if we went to Israel, Noiach. Maybe.”

“Sure,” I said, giving her that.

author bio

Noah Lederman is the author of the memoir, A World Erased: A Grandson’s Search for His Family’s Holocaust Secrets. His travel writing has been featured in the Economist, the Boston Globe, the Washington Post, and elsewhere. He writes the travel blog Somewhere Or Bust. He tweets @SomewhereOrBust.

Noah Lederman is the author of the memoir, A World Erased: A Grandson’s Search for His Family’s Holocaust Secrets. His travel writing has been featured in the Economist, the Boston Globe, the Washington Post, and elsewhere. He writes the travel blog Somewhere Or Bust. He tweets @SomewhereOrBust.

This was a really wonderful read, Noah.