How Travel Helped Me Find Solace In My Grief

How Travel Helped Me Find Solace In My Grief

“Take nothing but a camera,” said Pravar, our Intrepid group leader. “Security measures at the Taj are strict, and strictly enforced.”

Nailed behind the bus driver was a sign: Prohibited Items at the Taj Mahal. On it were twenty-four pictures (three rows of eight), each circled in a thick rim of red, each cut through with a red diagonal line. Pictures so small you could hardly decipher even one. Still, Pravar had me worried. Dressing that morning, I’d considered stashing the tiny jar of her ashes in my bra. Or my hat.

Rachel, my 23-year old daughter, was an avid traveler in life. She had one dying ‘wish’: to keep exploring the world. That, of course, was why I was here. The Taj Mahal has for years now lured travelers with the mere sound of its name. But I had a more personal reason.

“One day I’m going there,” she’d said, opening the book that Christmas morning to the picture of the Taj Mahal.

In Rachel’s final weeks I pulled down the book from the bookshelf and lay down beside her.

“Do you want to look at this?”

She nodded, yes. Her cheeks were flushed and swollen from the flood of steroids in her failing body. Her speech was almost gone.

The pages still smelled new. In blue pen, she’d drawn stars, five-pointed stars, beside the Grand Canyon, the Alhambra, Chichén Itzá, Venice, Manhattan, Santorini, Uluru, the Great Barrier Reef. I turned the pages quickly of those she’d miss: Temples of Angkor Wat, Zanzibar, St. Petersburg. When I got to the Taj Mahal I stopped and turned to look at her.

“Are you okay with this?”

She smiled.

“Your camera,” she said curtly, “remove the case.” Another guard patted down her friend. My mind was a flurry. How would I explain myself? To have come all this way.

From where I was standing I could already see the long rectangle of water which I knew so well from photos. I dropped my cross-shoulder bag onto the long table, the jar hidden inside an inner zipper pocket, turned away and struck up a conversation with two women in my group.

Surely, I wouldn’t be the first person smuggling ashes past security. The Taj was built in love’s memory. I imagine I’m part of an endless chain of people who have for centuries made the pilgrimage to this site to perform an ageless human ritual – the scattering of ashes.

“Madam, here’s your bag.” And there it was, my canvas bag of orange stripes, waiting for me to slip back over my shoulder. I walked on, bit down on my lip, whispered:

“We made it.”

In 2011, eighteen months after my daughter died, and still reeling from grief, I quit my teaching job, put my few belongings into storage and set off overseas, alone. Other than a confirmed two-month stay in a tiny Spanish village, there was no agenda. After that I let the winds carry me away in a kind of blind surrender.

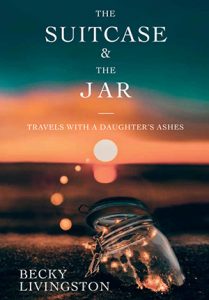

For 26 months I traveled with my daughter’s ashes (most of them) hidden inside my suitcase, house-sitting or staying with friends and family around the world. A tiny plastic jar is what I used to carry her ashes on my daily outings.

People called me courageous for leaving. It’s not how I saw it. I thought of it as faith in second chances. Travel’s appeal is that it’s so life-affirming. It forces us to see the world with childlike curiosity, and we discover that beauty is woven into everything around us if we take the time to slow down and pay attention. I’m thinking of the children in India, desperately poor, whose smile was a routine miracle.

Living out of a suitcase for two years helped me see how much simpler and softer life can be when we let go of all its trappings. Grief does that – it makes you question everything. You get clear on what matters most and how you want to live going forward.

Over time a sense of gratitude washed over me. Gratitude for what I did have, not for what I didn’t.

And house-sitting worked for me. Gentle travel, I called it. It meant being somewhere, not just seeing somewhere; geography lessons unlike those I’d learned in school. There was added value, too. It was affordable. House sitting allowed me time for contemplation, for space to stay with my grief, often when I wished it otherwise. The social life with friends and family was noisier, and often, a great deal more fun. The balance – aloneness and togetherness – felt just right.

These homes (29 in all) became my home. And just like Rachel’s ashes, they were scattered across the planet. Give me a map of the world and I can mark an X in each spot.

Nothing can fix what is foundationally irreparable, but fulfilling her dying wish to keep traveling was, above everything else, what helped me find solace in a world without her.

I love that she’s traveling even now.

In 2011 her life took an unconventional turn. She quit her teaching job in Vancouver and set off on what became a two-year pilgrimage. Originally from England, Becky now lives and writes in Nelson, B.C. You can find her on Facebook, Instagram and through her website beckylivingston.com.