Domestication Syndrome

Domestication Syndrome

“Domestication Syndrome” is a theory that was developed by Charles Darwin well over a century ago. The basic belief is that physical changes occur in mammals after being tamed for some time, and in many cases, the changes are not positive ones. When I stumbled on an article about it a short while ago, I quickly sunk into thought and began considering the changes that Pete and I have seen in ourselves over the past couple of years.

(Of course, the official theory is completely without bearing in our case, as our “wild” time and “domestication” time are but mere seconds in the grand scheme of life. We cannot prove anything absolutely, and most of the suggested changes have definitely not taken effect. Examples: I don’t think the size of our teeth has reduced, nor have our ears gone from erect to floppy. But being the unscientist that I am, I have decided to cherry-pick points in support of Darwin’s theory as they fit my own arguments and assumptions about our re-domesticated life.)

Increased docility and tameness

From roaming wild to being surrounded by boundaries, it is natural that some degree of submissiveness should follow. Pete and I went from throwing darts at maps to determine our next destination to spending most of our time in one spot. Like any mammal, we struggled with the new constraints. At first, we endeavoured to travel as much as my body and my treatment schedule would allow (sometimes, to a breaking point), but for the first time in almost a decade, we have a house to return to. We have a space to call our own. And as the days roll on, we are becoming much more comfortable here and have begun using the word “home” with much more ease.

We’re still traveling – I barely spent a day of September at home – but it is lessening. July and August were mostly quiet. October has been, too. For half of November I will be on the road from Saskatoon to New York to Montreal to Rhode Island, but it’s not by random choice or just because I fancy Montreal bagels (food cravings were often a determining factor in the past). Work will pull me to most of those places. I have been given fantastic opportunities to advance our business and I am grateful for all of them, but I do miss almost entirely traveling by whim. A trip to Mexico in early December with friends will help solve that desire, but it is a far cry from what we used to do.

So yeah, we’re definitely tamer. Or lamer? Both definitions might apply.

The test right now is to challenge ourselves in new ways and find enjoyment within our boundaries. (And to remember that being settled is the best thing for me. I still need time to heal.) We’ve found ourselves returning to activities that we used to do in our former “settled” lives. We’re both curling again and relishing it, even if the sport is much more painful than I ever remember it being. My body does not have the strength it once did, and I even sprained my damn thumb just in the act of throwing a stone. (For those of you who think curling is not physically demanding, I suggest you read this. Although I may be an extreme case – I think it is probably safe to assume that a sprained thumb is the weirdest curling injury ever recorded.)

As for the docility – being more “teachable” – Pete is embracing this fully by diving into increasing his cooking skills. Access to a full kitchen isn’t something we’ve had often in the past, but he is fully making the most of it now. Between balancing work and just resting my brain (it often “gives out” by mid-afternoon, although it is getting better everyday), the only expertise I’ve developed is in which TV series are worth binge-watching. However, I am sure that I can declare myself a better baker after indulging in the full series of The Great British Bake Off. Does that count?

Prolongation in Juvenile Behaviour

Maybe we haven’t quite prolonged our juvenile behaviour, but in some cases we have returned to it.

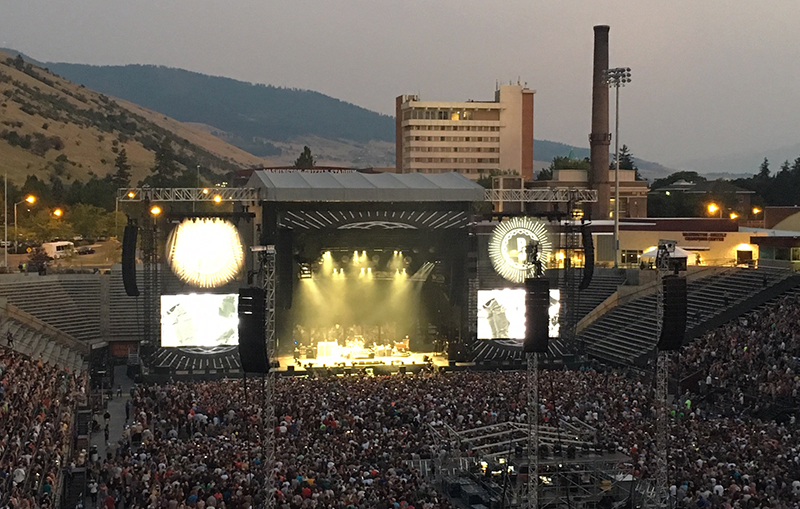

The other day, Pete went I went to a movie and I slipped into my new Pearl Jam t-shirt and a thick plaid jacket. The 90s are back, my friends, but for me, they never really left. I’ve always been a grunge-rocker at heart.

Although I guess it’s not entirely truthful for me to say that they never left. I didn’t carry one rock shirt with me for our eight years of nomadic travel, and that thick plaid jacket definitely would have taken up too much space in my backpack. Neither have the versatility demanded of travel clothing. Both would have been downright impractical.

But now I have a home to store things in. Nonfunctional clothing is an option once again, and I find myself drawn to a style of my youth, presenting another hallmark of our domestication syndrome. Some may say that I have passed the age of juvenility that allows for rocker shirts to be worn, but to that I say screw it. (As maturely as possible.)

Alterations in adrenocorticotropic hormone levels

This hormone causes the production of cortisol. Too much of it causes high blood pressure. I’ve been on medication for high blood pressure for over almost two years. Logically, this is because I have higher stress due to lack of travel.

(Errr, most likely this increase in blood pressure is because of medication I took during treatment – arsenic, specifically – but remember, I am using whatever loose association to Darwin’s theory that I choose.)

Reduction in total brain size

Science says that travel makes you smarter.

Of everything that has happened to me in the past two years, the absence of the challenges of travel is what stings most severely. I miss being confronted by language barriers, figuring out routes in new cities, and meeting others whose viewpoints expand my own. Some of that can be achieved locally, but instances are few and far between.

I am not learning as much about the world. Or about myself.

Will this lack of exposure to all things foreign actually cause my brain to shrink? Perhaps not physically (such things take a really LONG time), but symbolically? Yeah, I think it already has. As a kinesthetic learner, not being constantly confronted by new places and cultures has definitely decreased my intake of knowledge.

Coat colour changes, alterations in craniofacial morphology, changed concentrations of several neurotransmitters, and more.

So perhaps this is the best place to stop my theorizing, as I would definitely be grasping at straws to draw a connection between these last few. (Although I *did* buy a new coat the other day. It’s black and white; my old one was blue. What does THAT mean?)

The more time that goes by, the more settled we have each become. Rocker t-shirts are calling to me. The Great Canadian Bake Off is now a thing and must also be watched. I really enjoyed being home for October. And we now have this other domesticated animal that makes the thought of leaving hard to bear because he is so damn cute.

All of these changes are not necessarily bad. And guess what? They can be changed again.

Darwin’s theory goes onto say that if domesticated animals are released to the wild, some of these traits would be lost over time. (A shrunk brain may take up to 40 generations to reverse, however. We have to be careful not to wait too long.)