Stories of the New Brunswick Acadians

Words by Dalene Heck / Photography by Pete Heck

It is one thing to wander museums. There’s something romantic about lingering in long halls and getting lost among the illuminated rooms with an array of intriguing displays. In the best of them, inspiration happens too.

It is quite another thing to insert yourself in the time or place that you are longing to learn of, and to quite literally sink your hands into an age gone by. Or to be so captured by an enigmatic entrepreneur who creates on the very land his ancestors once worked, and then wraps his product in artful recreations of historic stories to help ensure his consumers never forget.

In discovering the history of a new place, the experiences that stick are those one can immerse themselves in. That’s where the greatest learning and the most inspiration happens.

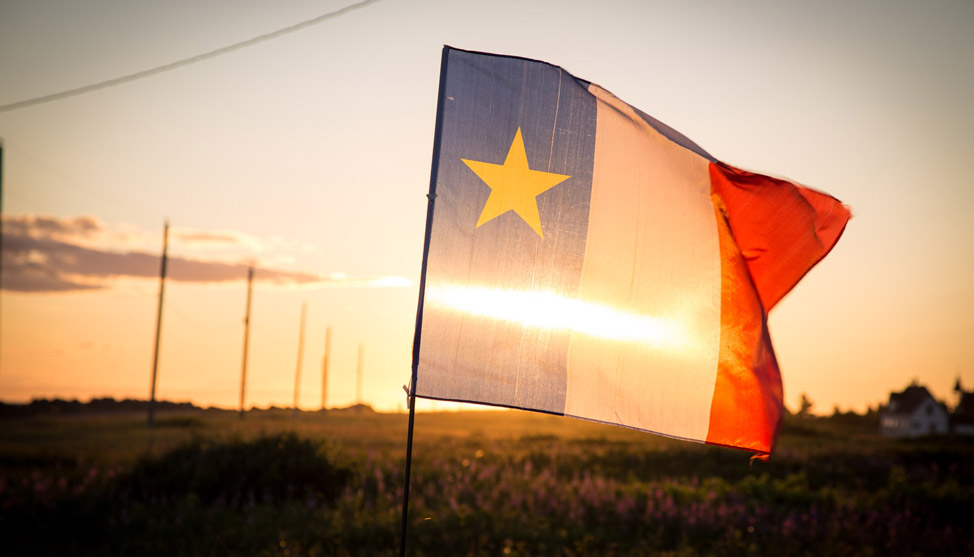

Which brings us to our time along the Acadian Peninsula in northern New Brunswick, and our quest to learn more of the history of the Acadian people.

Acadians in New Brunswick

Village Historique Acadien

Historic villages such as this have become a mild obsession for us. They are something we’ve routinely driven by without a thought in the past, but one entertaining stop here last year encouraged us to seek them out. Since then we’ve been to several and they all have the same effect: they prompt a desire to return to a time long gone, to step into long petticoats or start milling flour by hand. (If there are such a thing as past lives, then I was definitely a new settler somewhere. The Laura Ingalls Wilder instinct in me is a strong one.)

We walked with purpose through the Village Historique Acadien just before it opened, hot on the heels of Madame Savoie, who was to be our historic guide for the morning. She was in period clothes: a full skirt and long-sleeved shirt of muted colours, and of course topped with a kerchief. When we arrived at the small cabin I was slightly disappointed that similar clothing wasn’t available for us (not to be braggy, but I am pretty confident at my ability to rock a kerchief).

Still, we were quickly immersed in the experience of life in the Savoie house that dated back to 1855. The two rooms on the main floor, and additional one upstairs, housed 14 people. The house and land had been passed down for several generations; the family landing there when British soldiers chased them out of their original home.

Madame Savoie put us to work with two major tasks: the first was the making of moise, a savoury dish of potato, turnip, pork and onion. We sliced the fatty pork and grilled over the fire, later using the grease to caramelize the onions and soften the starches. The final product was hearty and of mellow flavour, although not the most appetizing to look at. It lacked a diversity of colour that prompted us to ask about the addition of carrots to make it pop. But carrots hadn’t made it to the village yet in 1855. They worked with what they had, and at times, were probably lucky to have this much.

Dessert was on the menu as well. Pete dug his hands in the simple dough, rolling it out to line the bottom of the dutch oven and a layer on top. The apples were browned with sugar and butter for filling. With no conventional oven, the oven was placed over hot coals from the fire, and a scoop of coals were also placed atop the lid. The cooking process took no more or less time than a standard oven, and the aroma brought in other village visitors by the droves. Madame Savoie recounted the story of her house each time new people popped in, while we sat salivating and then finally, eating. We rolled out of the house just after lunch, stuffed of food that would stick with us for hours.

After bidding Madame Savoie adieu, we wandered the rest of the village and were transported throughout 1770 to 1949. We made one more stop to taste a local drink of pijoune (also referred to as a “homemade medicine”), and otherwise known to us as a hot toddy. The bartender was suited to fit the era he represented, and well knowledgable of this liquor he served, and our conversation as such quickly led us to the discovery that he was strongly connected to it. The gin he served in the pijoune, from the local distiller Fils du Roy, was the product of his son, who we were going to meet next.

Distillerie Fils du Roy

Several days later we found ourselves inside a growing distillery in the small town in Paquetville. Sébastian Roy, with his salmon collared shirt under blue overalls and black rubber boots, was the son of the Village bartender, the overseer of the distillery, and the mastermind behind the product.

“Imagine when you are 14 years old and you create life,” Sébastian explained the beginnings of his passion as we toured through the Distillerie Fils du Roy. At that young age, he had been reading old encyclopedias and found himself fascinated by the fermentation process.

And so he began with a jar in his closet. He was excited by his own results (without tasting it, after hearing warnings of the “blinding” effects of alcohol), and the passion continued to grow. Sébastian attended university not for science but for business, his dorm closet was again his laboratory, and he became more cunning in covering up the smells that emitted (the best method was to place a Bounce sheet over the air register).

The main thing he learned in school, according to Sébastian, was that “when you make alcohol at University, you have a lot of friends.” He documented his friend’s hangovers to adjust recipes. When his parents came to visit and buy groceries for him, he loaded up the shopping cart with sugary stuff to aid in his brewing.

It should be no surprise then that he later opened his own brewery in Moncton. The idea for the distillery came later. When his mother lost her job, he suggested that they create Fils du Roy together, and when she saw his enthusiasm for the plan, she agreed.

The land the distillery sits on once belonged to his great great great grandfather. He uses it to grow his own peat and absinthe, and hopes to someday also grow his own rye and malt. Spirits remain his passion, but as there is a bigger demand for beer, he produces both. Several rooms have been added on since it was opened and they quickly outgrew their space. As Sébastian tells us the history, we are standing in a large tasting room that is nearly finished. He gestures to the walls behind us to show where not only his own products will be displayed, but so will others from the area. Each region of Acadia will be honoured with named benches.

The distillery itself was interesting given Sébastian’s flair for storytelling and his desire to make things to particular specification using only New Brunswick crafted products and equipment. However, where he really captured us was in how he purposed the historic stories of the Acadian people with what he produced. Each bottle is based on a story.

Like each of the beers Evangeline and Gabriel, which pulled elements from the Longfellow poem “Evangeline” that has been embraced as emblematic of the Acadian people. It’s a love story, and the beer reflects that. Each taste fine on their own, but when the beers are poured together in a glass, they taste even better.

Or the ice beer, where instead of heating, it is set to -8C, giving it a crisp and distinct flavour. The label that adorns it is based on a historic north-south train from Caraquet that was famous for its unreliability.

And especially the gin, with its many deserved awards and a fantastic story of its own. It is made with eastern white cedar, which is one of the first documented botanicals in North America. Given its high level of vitamin C, it was used to cure Jacques Cartier and his crew of scurvy on one of their historic voyages.

We left the distillery inspired by Sébastian’s stories and with heavy bags of the beer and liquor we purchased inside. Each carried valuable historic lessons, but most importantly, a reminder of his enthusiasm for the life he created.

How to Do It

Village Historique Acadien is open year-round with a variety of offers to experience the Village in new ways. Cooking lessons with Madame Savoie are only available during the summer months.

Do not miss out on a visit to Distillerie Fils du Roy, especially with the new tasting room that will have opened since we visited.

This post was produced by us, brought to you by Tourism New Brunswick.